Selma, the Voting Rights Act, and the Freedom to Vote

2025 marks the 60th anniversary of Bloody Sunday, the historic day when civil rights activists attempted to march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, but were violently stopped by law enforcement.

The horrors of Bloody Sunday, broadcast across the nation, led to the signing of the most important and impactful civil rights legislation in our history. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) marked the first time that access to the ballot was genuinely available for all American voters, directly addressing racial discrimination in voting. The success of the VRA and its protections for voters today is thanks in major part to the activists who marched on Bloody Sunday.

Tell Congress to Support Voting Rights Today!

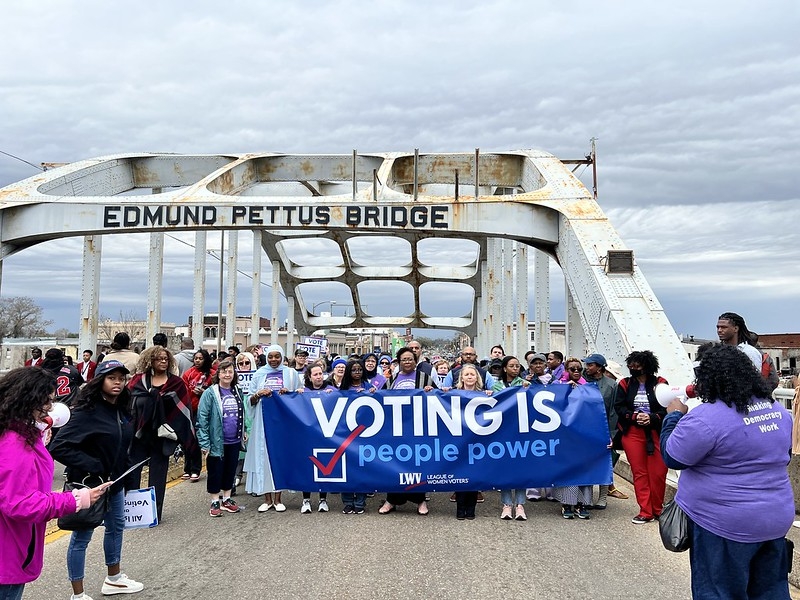

To commemorate this pivotal moment in voting rights history, in March 2025, civil rights activists gathered in Alabama to continue the fight for voting rights at the very location the foot soldiers marched decades ago. The League showed up in full force in Selma to stand alongside leaders and organizations protecting the hard-won right to vote. While inspiring and mobilizing, the event also served as a space to remember and understand the dangers of today’s attacks on voting rights.

Today, as we examine our current state of voting in the US, it’s crucial to see how our history led us here and what we can learn. Examining the relationship between voting access and racial discrimination can help us understand why the League and others are fighting for new voting legislation that further protects voters against prejudice.

How Slavery, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow Impacted the Right to Vote

Like many systemic issues in America, voter suppression is rooted in slavery. Only white, property-owning men had the right to vote through the Civil War. Even after the war ended in 1865, it took the Reconstruction Amendments to abolish slavery (Thirteenth), institute equal protection under the law (Fourteenth), and grant the right to vote to Black and other non-white men (Fifteenth).

Despite (or perhaps because of) constitutional protections for the right to vote and participate in politics during the Reconstruction Era, states created new barriers to voting for Black men. Jim Crow laws effectively blocked Black voters at every step: from registering to vote to casting a ballot to counting that ballot. Suppressive laws enabling poll taxes, literacy tests, and the “grandfather clause” came into existence across the country. On top of these, white people (including political leaders and law enforcement) used intimidation and physical violence to stop Black men from voting.

As a result, by 1940, 80 years after the start of the Civil War, only 3% of eligible Black voters in the South were registered to vote.

Voting Rights Activism: Freedom Summer and Bloody Sunday

While states and localities in the Jim Crow South largely ignored the requirements of the Fifteenth Amendment, in the mid-twentieth century, civil rights groups began pushing for actual voting rights. Groups like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Southern Christian Leadership Coalition (SCLC), the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) organized boycotts, marches, voter registration drives, and public education campaigns to encourage Black Southerners to vote.

Two well-known events, Freedom Summer and Bloody Sunday, were critical in raising national awareness of and supporting voting rights within the Civil Rights Movement.

In the summer of 1964, civil rights groups organized Freedom Summer, in which 1000 out-of-state volunteers joined thousands of Black Mississippians to hold meetings, protests, teach-ins, and voter registration drives highlighting the disenfranchisement of Black voters. The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) was formed during this time to increase Black representation at the Democratic National Convention.

During the summer, local officials and white residents arrested and beat Freedom Summer workers. They burned and bombed churches, Black homes, and businesses. Notably, the KKK murdered three civil rights workers, including two New Yorkers, which drew attention to the cause from the North.

Bloody Sunday occurred on Sunday, March 7, 1965, on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. In the aftermath of the Alabama state troopers’ murder of civil rights activist Jimmie Lee Jackson in February 1965, over 500 protesters gathered in Selma to demand the right to vote. They planned to march over 49 miles from Selma to Montgomery and hold a rally on the steps of the state capital.

Led by Representative John Lewis, Hosea Williams, and others, the group began marching across the bridge. Immediately, Alabama state troopers and white vigilantes on horseback stopped the protesters. They deployed tear gas and attacked protesters with clubs, injuring hundreds of non-violent marchers. The media aired the violent scene occurring in Selma, which galvanized public support. ABC News interrupted its own broadcast of “Judgment at Nuremberg,” which almost 50 million Americans were watching, to show the footage from Selma. Within two days of Bloody Sunday, demonstrations protesting the brutality sprang up across the country.

A week after Bloody Sunday, on March 15, 1965, President Johnson addressed Congress to introduce legislation protecting the promise of voting rights contemplated in the Fifteenth Amendment. He said, “[t]his bill will strike down restrictions to voting in all elections — federal, state, and local — which have been used to deny Negroes the right to vote. It is wrong — deadly wrong — to deny any of your fellow Americans the right to vote in this country.”

President Lyndon B. Johnson and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. at the signing of the Voting Rights Act

On August 6, 1965, less than six months later, President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) into law, highlighting the direct link between the activism in Selma and voting rights.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965

The VRA is one of the most effective civil rights laws in history. It was passed to block Jim Crow policies in the South, enforce the promises of the Fifteenth Amendment, and dismantle discriminatory structures across the United States pertaining to voting. As explained above, the bill emerged from a nonviolent campaign for voting rights that was repeatedly met with state violence.

Since its passage, the VRA has been wildly successful in protecting against the suppression of Black voters. Its various sections protect against illegal redistricting and gerrymandering, voter intimidation, and suppression tactics like poll taxes, literacy tests, and the grandfather clause.

One of the most effective sections for remedying the evils of racial discrimination in voting was Section 5 of the VRA. Section 5 required specific states and local governments with histories of racial discrimination to get federal approval, or “preclearance,” to change any voting law. This step was meant to ensure discriminatory laws never went into effect.

Whether a state or locality was considered a “covered jurisdiction” by Section 5 depended on its history of racial discrimination. The formula for determining the coverage was mapped out in Section 4 of the VRA. These two sections worked in tandem to keep historically discriminatory states and localities from reinstating pre-VRA laws that allowed them to discriminate against voters of color.

Attacks on the VRA: Sections 2 and 5

Despite the voting rights strides resulting from the VRA, various portions of the law have been weakened through litigation in the last 60 years.

Section 2 of the VRA makes it illegal to use voting practices and election administration rules to discriminate against people based on their race, color, or membership in a language minority group. This includes the prohibition of vote dilution, which results in minority groups having proportionally less ability to elect government officials of their choice based on how their districts are drawn. It also includes vote denial, which concerns laws that discriminate against voters related to the times, places, and manners of elections.

In Brnovich v. DNC, the US Supreme Court made it significantly more difficult for voters and organizations to successfully challenge laws that result in vote denial on the basis of race. Thankfully, in Allen v. Milligan, the Court upheld Section 2 in a vote dilution case regarding racial discrimination in the drawing of Alabama’s congressional map.; However, a current case at the US Supreme Court, Robinson v. Callais, places Section 2 in the crosshairs again. The League submitted an amicus brief to the Supreme Court with partners in December 2024 calling on the court to uphold Section 2.

However, few decisions have been as harmful as the destruction of Section 5 preclearance in Shelby County v. Holder. As our CEO Celina Stewart explained in a previous blog, the Supreme Court’s 2013 decision in Shelby County v. Holder was a devastating blow to the VRA.

It can be challenging to grasp what the majority in Shelby did; however, Justice Ginsburg illustrated it perfectly (in a well-known dissent) when she said, “[t]hrowing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.” In other words, you have a tool to fix a problem, and because it works well, you think the problem no longer exists and the tool is unnecessary.

The court’s willingness to declare the preclearance unconstitutional because it was working correctly led to immediate increases in restrictive voting laws in the places chosen for preclearance due to discriminatory histories.

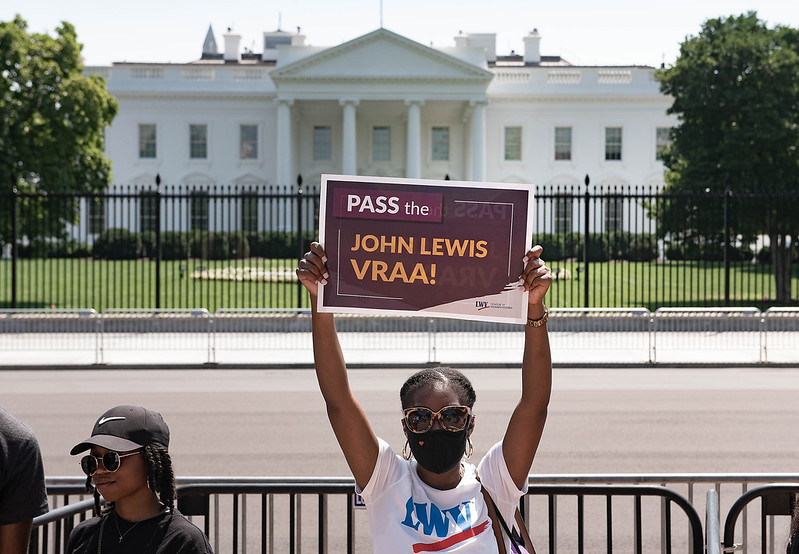

New Voting Rights Legislation: The John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act

In response to the Supreme Court severely weakening the VRA, Congress must pass legislation to restore the law to its full purpose. The right to vote is a fundamental one. To build a better democracy, every person must be able to cast a ballot and have that ballot counted equally, no matter who they are or where they live.

Congress must pass the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act (JLVRAA) to restore the VRA and fight increasing attacks on voting rights at the state level. The bill would specifically respond to the SCOTUS cases mentioned above, including creating a new coverage formula — which the Supreme Court instructed Congress to do in its Shelby County v. Holder decision.

On March 5, 2025, in remembrance of Bloody Sunday and the fight for equal voting rights, Representative Terri Sewell (AL-07) reintroduced the JLVRAA. The League and over 140 other organizations announced support for the bill. LWVUS CEO Celina Stewart also spoke at a video press conference to share the League’s appreciation that Rep. Sewell brought this crucial bill back to the House floor.

The United States cannot stop fighting for federal protections for voting rights. Yet because the federal government has failed to restore the VRA, states that value voting rights are also stepping up to safeguard the right to vote.

State-Level Voting Rights Acts

Passing state-level voting rights acts (SVRAs) is an incredible way for states to build upon voting rights protections. SVRAs allow each state to enshrine voting rights into law in the way that best fits its unique needs. So far, eight states have passed their own voting rights acts, including California, Connecticut, Illinois, Minnesota, New York, Oregon, Virginia, and Washington. SVRAs have also been introduced in the Arizona, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Maryland, Michigan, and New Jersey state legislatures in the 2025 legislative session. Currently, Colorado and Maryland are the only states in which SVRAs could make it to the gubernatorial desk this session.

These SVRAs include provisions seen in today’s VRA as well as updated protections. For example, some SVRAs have language-assistance provisions and prohibitions against vote denial and dilution. The three most recently passed SVRAs — Connecticut, New York, and Virginia — built preclearance programs into the laws. After Shelby, including preclearance in state law may be the most effective way to revive the program that effectively prevented discrimination.

Overall, the SVRAs enshrine stronger voting rights protections for state residents.

How You Can Support Voting Rights Today

Throughout the League’s 105-year history, the organization has worked to empower voters and defend democracy. Unfortunately, the fight for our democratic system of governance and equal access to civil rights and liberties is being tested. As voting rights opponents work harder to suppress the vote of people of color through gerrymandering, strict voter ID laws, restrictions on election administration, and disinformation, it is imperative to activate and push toward an actual representative, multi-racial democracy. Silence and passivity will not help us move forward. Instead, failure to act in this moment will reverse our efforts, putting the nation back centuries.

To join the League in defending our democracy, here are some concrete actions you can take at the federal, state, and local levels:

Federal

- Call your representatives and urge them to support the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act

- Tell your representatives to oppose the SAVE Act

State and Local

- Join coalitions working on constructing and passing state voting rights acts to protect your community’s right to vote, like your local League

- Fight against stricter voting requirements in your state’s legislature (you can find anti-voter bills through the Voting Rights Lab)

The Latest from the League

As activists gathered in Selma on Sunday to reenact the steps of marchers like John Lewis and Martin Luther King, Jr., we are reminded that the fight for voting rights is as alive today as it was in 1965. Indeed, the landmark law that passed after Bloody Sunday — the Voting Rights Act of 1965 — is in critical condition.

This block reviews the racist origins of the Electoral College and why it still hurts Black Americans and other communities of color to this day.

Bloody Sunday refers to the day in 1965 when hundreds of civil rights activists were attacked by law enforcement while marching for Black American's right to vote. Now, Bloody Sunday is an observance where civil and voting rights advocates congregate to honor the legacy of the original foot soldiers who risked their lives for equal rights. Jubilee attendees build on the original activists’ legacies by continuing to fight for equal representation.

Sign Up For Email

Keep up with the League. Receive emails to your inbox!

Donate to support our work

to empower voters and defend democracy.